Calligraphy by Mehmet Shefik, Ulu Camii, Bursa, Turkey.

Since selling or mostly giving away my possessions, save some of my library, papers and singular and precious things such as family photographs, art works of my son, myself and others - putting all this in a five-by-five foot storage locker - I have been living out of a suitcase, staying in hotel rooms (mostly) or with friends for almost a year now. I feel the reality of this renunciation each day, though I can't claim it as an especially heroic act. I was a lousy homeowner and am so easily distracted (or subject to multitasking) that it has only been through simplifying my life to this seemingly utmost degree that I can achieve any kind of focus (that feels right in my heart). Another way of putting it is cultural speed and my need to slow down have kept me on a surfboard rather than a boat, which is precarious and visceral and gives me a chance to get to the "fundamental principles" (as a surfboard would tell the rider more about the ocean than a passenger in a boat). This is also how I feel about meditation, that is is something fundamental, and so I always shared Gary Snyder's statement about mediation in the classes I taught at Naropa University:

Meditation is fundamental, you can't subtract anything from that. It's so fundamental it's been with us for forty or fifty thousand years in one form or another. It's not even something that's specifically Buddhist. It's as fundamental a human activity as taking naps is to wolves, or soaring in circles is to hawks or eagles. It's how you contact the basics and base of yourself.It is precisely this sensibility that animates the passion of my exploration between the teachings of Lord Mukpo and those of Ibn 'Arabi, between Buddhism and Islam, and between the so-called profane and the so-called sacred - which I continue this week with a series of photographs and prose entries, taken and written from surfboard.

Quote from The Real Work: Interviews and Talks,

1974 to 1979, by Gary Snyder. Pg. 83.

1974 to 1979, by Gary Snyder. Pg. 83.

COPY

While I was walking down Tophane Iskelesi Cadessi I turned to the right and saw a wall and on it a poster and I made a copy of a portion of it ("copy" is how my photographic hero Daido Moriyami speaks of what the camera does): the woman above. This photograph stayed with me as one I wanted to write about, to decipher its symbol. I left Istanbul and traveled to Bursa and during yesterday's breakfast I read a sentence that the photograph seemed to be waiting for: The intermediary "symbolizes" with the worlds it mediates. In the word decipher, "de" expresses reversal and "cipher" is a figurative person or thing of no importance (one who does the bidding). This particular meaning of cipher comes about because cipher itself traces to the Arabic ṣifr or zero. Yesterday I read the quote on symbolism and today over breakfast, unknowingly, I wrote down the Turkish word for zero, which is sıfır. Now I am at the moment where the etymological synchronicity with events and their time sequence has became a platform suspended in air (I have vertigo). Symbolism is a form of dance where the partners change unexpectedly and you just have to stay with it.

[The intermediary "symbolizes" with the worlds it mediates. Pg. 216, Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sufism of Ibn 'Arabi by Henry Corbin.]

ECHO

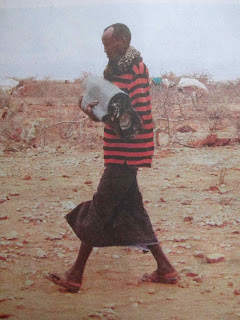

This is a photograph I took of a photograph I came across in the Hürriyet Daily News earlier this month. The original picture was taken by an unnamed Reuters photographer whose connection with the man shown in the photograph was visceral or primary. The photographer's photograph was copied by the newspaper and now by me; an echo of an echo of a starving man walking somewhere in Somalia, with his dead child wrapped in what looks like the remains of a cardboard box. Photographs could be called intermediaries and I have stayed with this one. It calls out for causes, and the article sites this most immediate one: drought. "It should be the rainy season" but no rain is falling. Other immediate causes are displacement by war and less directly rocketing food prices as global demand increases, commodity speculators manipulate markets, supplies dwindle and as wealthy countries (as well as individuals) buy vast tracts of land in Africa and other less "developed" countries to guarantee food for their own people. Ever increasing tracts of farmland in, say, Sudan or Kenya is now owned by China or Saudi Arabia, and local farmers are displaced from the land and countries are dispossessed of their own farming resources. Global warming will increase drought and desertification, especially in Africa, all of this making the man in the photograph an intermediary of the highest order. Membranes are typically so thin they seem miraculous and unbearably vulnerable: our skin and the blood so close to the surface, so easily spilled; topsoil, so meager compared to the earth's diameter to be laughable; our atmosphere that once seemed so infinite.

ENVY

I took a passenger ferry from Istanbul to Bursa. I thought I purchased a window seat but what I ended up with was a seat against a wall, below a television monitor and facing the other passengers; the perspective from which I took this photograph (it seems a small point-and shoot-camera can be used almost anywhere now; no one notices, no one cares). The woman in the center of the photograph was cloaked in a burqa; it was not just her dress but how she held herself that contrasted so greatly with the woman beside her, attired without elegance and slumped in her seat. Putting aside the complexities and furor of debate about the burqa (which exist everywhere, including or especially Muslim countries), and how difficult it is to confront from a feminist perspective (my own), in that moment, for that moment, I envied her. What an experience to be invisible to others and thus take up no social mask, as well as be freed from having to engage in small talk (though traveling in Turkey has left me largely without either the mask or the talk). I studied her as I could because she impressed me in other ways and my potential to judge or dismiss became instead to inquire: this woman was in individual human being and therefore, as we all are, a mystery comprised of complexities who ultimately thinks like no one else (not even herself). Soon after the ferry embarked the woman opened her Quran and read it for the entire journey. To read something that demands contemplation is itself a form contemplation, and potentially to be admired. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the secularist founder of modern Turkey, dismissed Islam and once claimed the entire "Turkish nation resembled those who commit the Quran to memory without understanding the meaning of a single word and thus becoming senile." Atatürk's view was materialistic in the way Lenin's was (in the way modernity en mass is) and set one wave of history into motion. Removed from historical-political generalizations, I sat in the anecdotal, seat 324 of the Yenikapi-Bursa ferry, and observed the other passengers. The woman in the burqa carried a potency, a high-frequency focus, quite ennobled. Her clothing extended to her hands, the black gloves she turned the pages of her book with.

Quote from Atatürk: An Intellectual Biography,

by Sükrü Hanioglu. Pg. 132

SEED

Ulu Camii, Bursa, Turkey.

Nearly two years I bought a book by Ibn 'Abrabi (Journey to the Lord of Power: A Sufi Manual on Retreat) that was illustrated with reproductions of the "monumental mural compositions" by Nineteenth Century calligrapher Mehmet Shefik. The racing freedom of Arabic had always appealed to me, particularly in these highly stylized and energized works. The text explained the calligraphies were made for Ulu Camii (Grand Mosque) in Bursa, Turkey. And now, because of the book, I was standing in front of them, photographing them, experiencing the reality of Ulu Camii.

My "reality" of Ulu Camii consisted of the plastic bag I had wrapped my sandals in and now carried in my left hand, and of a rapidly decreasing sense of self-consciousness. My experience inside the mosques I've visited - including the prayer ceremony I once took part in - is one of solitude and fraternity, and that the mosque, in its greatest conceptions (as Chartres, say, is to Christianity), is a space of inwardness, extremely personal even. Allah, the divine or the unconditioned not expressed so much though a vaulted ceiling (though some domes are huge) but in an intimate nook, the wall in front of one, or simply the carpet below, and that an ideal (or enlightened) "society" would momentarily occur not only as people prayed together, but as they congregated somewhat informally and haphazardly in the various sections of the mosque's omnidirectional space (the mihrab not being the "front" so much as a direction) and in these "gatherings" the highest conversational prajna (understanding, cognitive acuity, or wisdom) might occur, a Socratic salon that would not argue dogma but open portals beyond it.

I had sensed all of this eleven years ago when I visited the Cathedral and former Great Mosque of Córdoba. In that astounding work, 856 columns and countless arches create a labyrinth of contemplative space and here, in Ulu Camii, though the arcitecture was different the potential was not only the same, but continues to be realized (the Mosque of Córdoba no longer functions as a mosque but as a Cathedral and museum).

Inside Ulu Camii is a large ablution fountain which one may both wash and drink from at length. Outside the mosque I'd washed and drank from the ablution fountain there, and inside I drank again, making my reality water (its consciousness), there was a tangibility to this, as if I "entered" the Camii through the water. The "real" murals didn't impress me as much as when I'd seen them in the book (that seeing was the kind of imaginative moment or "transmission" that seldom arrives again in the form of a now-met external expectation-destination). I was transfixed by the welcome of the atmosphere and I felt in no way an intruder, nor did I detect the slightest glance of disapproval. Muslims often speak of Islam as a religion of peace and I felt a tremendous, palpable peace in the Camii, also very strong and potent. When I left Ulu Camii I experienced an unmistakable sense of being "changed" though a kind of blessing or spiritual grace, the same thing I felt in a single moment of Lord Mukpo's presence, or other great teachers of the Tibetan lineages.

TRACE

I took this picture of the surface of the Bosphorus when I was still in Istanbul, from a viewing platform at the half-way point of the Galata Bridge. The photograph suspends the movement of the water into a simulacrum of the mountain ranges found on land (or below the sea). My experience of the drala principle and the drala has often (unexpectedly) corolated with water (Boulder Creek, the River Arno, the Mekong) and so made me more devoted to water, its element, idea and necessity. I came down with food poisoning the day after visiting Ulu Camii and lay in bed for thirty-two hours, for much of the time unable to drink water because it made me vomit again. I slept most of it, two nights and the entire day in between - though I also woke up dozens of times. Each time I woke, it was as if I'd just been taken to an earlier time of my life in order to feel its particular suffering, duration, or epiphany: a certain hike I took in southern Utah when I was nineteen; a desk I worked at doing accounting; the first time I took my son to Mexico.

I've been working with this process for some time: writing down, if I remember to, the thought I have when I first wake, even if just from a nap (sometimes especially a nap) as if this was one of the moments Lord Mukpo's dream-time could spill in; as he once said, "All the relative thoughts that happen in your mind in connection with cause and effect are the agents of the dralas." Yesterday I was too sick to write anything down, but the whole episode aligned with a memorable and poetic statement by Antonio Gramsci I had read the day before, that history "has deposited you in an infinity of traces without leaving an inventory" and as part of becoming conscious it is necessary "to compile such an inventory."

I've been working with this process for some time: writing down, if I remember to, the thought I have when I first wake, even if just from a nap (sometimes especially a nap) as if this was one of the moments Lord Mukpo's dream-time could spill in; as he once said, "All the relative thoughts that happen in your mind in connection with cause and effect are the agents of the dralas." Yesterday I was too sick to write anything down, but the whole episode aligned with a memorable and poetic statement by Antonio Gramsci I had read the day before, that history "has deposited you in an infinity of traces without leaving an inventory" and as part of becoming conscious it is necessary "to compile such an inventory."

Quote from Orientalism, by Edward Said, pg 25.

. . . . . . . . . . .